Ronald Reagan, the beacon of modern American conservatism, believed in collective bargaining for government workers.

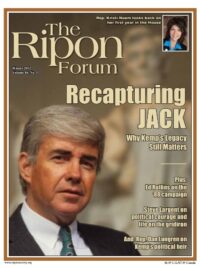

That’s right. Reagan, the president whom Governor Scott Walker invoked as his inspiration in February 2011 when he stripped Wisconsin’s public workers of their union rights, held views on collective bargaining at odds with those espoused by Walker and leading conservatives in the Republican Party in recent years. This is one of the most significant findings to emerge from my recent book, Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America.

Collision Course tells the story of the strike that helped define the Reagan presidency. Less than seven months after he was sworn in, President Reagan faced a walkout by the union of the Federal Aviation Administration’s air traffic controllers, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO). On August 3, 1981, PATCO rejected the administration’s final offer in a months-long contract negotiation and struck. Their action was illegal; federal workers have no right to strike. Reagan refused to continue negotiations with a law-breaking union. Instead, he laid down an ultimatum. If the strikers did not return to work within 48 hours, he threatened, they would be “terminated”—fired and permanently replaced. When more than 11,000 controllers defied him, Reagan made good on his threat.

That myth held that Reagan had sought out the confrontation with PATCO in order to deal a crippling blow to unions… To the contrary, the Reagan administration had hoped to avoid a controllers’ strike.

That event changed American labor relations. Never before had the country seen a national strike broken so swiftly and completely. Reagan’s success in defeating PATCO in turn galvanized many private sector employers who had long wanted to take on unions. In the years following the PATCO strike, many companies opted to replace striking workers instead of reaching settlements with them. As a result, over time the strike all but disappeared as a tool providing bargaining leverage for workers. In the 1970s, the U.S. averaged 289 major strikes per year. By 2009 that number had dwindled to 5.

The PATCO strike had such a devastating impact on labor that a myth soon arose around the event. That myth held that Reagan had sought out the confrontation with PATCO in order to deal a crippling blow to unions. This myth took root early. A story in The Nation magazine only months after the strike said it all: its headline read, “How PATCO Was Led Into a Trap.” But, as I show in my book, there was no plan to trap PATCO. To the contrary, the Reagan administration had hoped to avoid a controllers’ strike. It had enough headaches to deal with as Reagan pushed his legislative agenda in the summer of 1981. And no one was sure how badly a strike would affect the economy or air safety.

Not only was there no effort to trap PATCO, Reagan went further than any previous president had gone in negotiations with a federal union, a fact that was later obscured by his dramatic standoff with PATCO. Once the union made clear in June 1981 that it planned to strike if its demands were not met, Reagan approved a remarkable contract offer. Although federal workers had no right to bargain over salaries, Reagan made them a salary offer anyway. He offered PATCO an 11.4 percent increase in controllers’ compensation during a year when other federal workers would only see a 4.8 percent scheduled increase. If these numbers seem large to us today, it is because the country was in the grip of rampant inflation then: prices rose by 10.4 percent in 1981. (Indeed, the fact that all but 1 percent of their promised increase would be eaten up by inflation led the controllers to see Reagan’s path-breaking offer as inadequate—they were frustrated after years of watching inflation outstrip their scheduled salary increases.)

It is worth remembering today that even in the heat of his conflict with PATCO, Reagan never questioned the controllers’ right to bargain.

Yet Reagan’s offer was unprecedented. And he extended it not only because PATCO was one of the few unions to endorse him in 1980. He believed controllers deserved more. He was prepared to break new ground by offering them a raise, but he would not be pushed to sweeten his offer by an illegal strike.

It is worth remembering today that even in the heat of his conflict with PATCO, Reagan never questioned the controllers’ right to bargain. This should not surprise us. Reagan had formerly led a union, the Screen Actors Guild. And as governor he presided over the spread of collective bargaining for public workers in California through the 1968 Meyer-Milias-Brown Act. Thirty years of myth-making in the aftermath of the PATCO conflict has clouded the issue, but the fact is that Ronald Reagan believed in collective bargaining. As they clamor to don Reagan’s mantle, today’s increasingly anti-union conservatives ought to remember that.

Joseph A. McCartin, teaches history at Georgetown University. He is the author of Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America.